Tag Archives: Housing

Housing is a human right not a commodity

In Melbourne, Australia, one in five investor-owned units lie empty, the report says; in Kensington, London, a prime location for rich investors, numbers of vacant homes rose by 40% between 2013 and 2014 alone. “In such markets the value of housing is no longer based on its social use,” the report says. “The housing is as valuable whether it is vacant or occupied, lived in or devoid of life. Homes sit empty while homeless populations burgeon.” …

Farha, 48, by background a human rights lawyer and anti-poverty activist, calls for a “paradigm shift” whereby housing is “once again seen as a human right rather than a commodity”. It is clear, she suggests, that the UN’s sustainable development goal of ensuring adequate housing for all by 2030 is not only receding, but without regulatory intervention to re-establish the primacy of housing as a social good, laughably optimistic. Continue reading

Foreign investment increases house prices

Average house prices in England and Wales have almost tripled in the last 15 years, from just over £70,000 in 1999 to about £215,000 in 2014. Apart from a reduction in 2009, at the height of the global financial crisis, house prices increased every year during this period. Behind this average lies considerable regional variation, with average prices in the prime London area of Kensington and Chelsea reaching £1.3 million in 2014. Continue reading

Housing Bubble: 3 factors that determines the rent prices

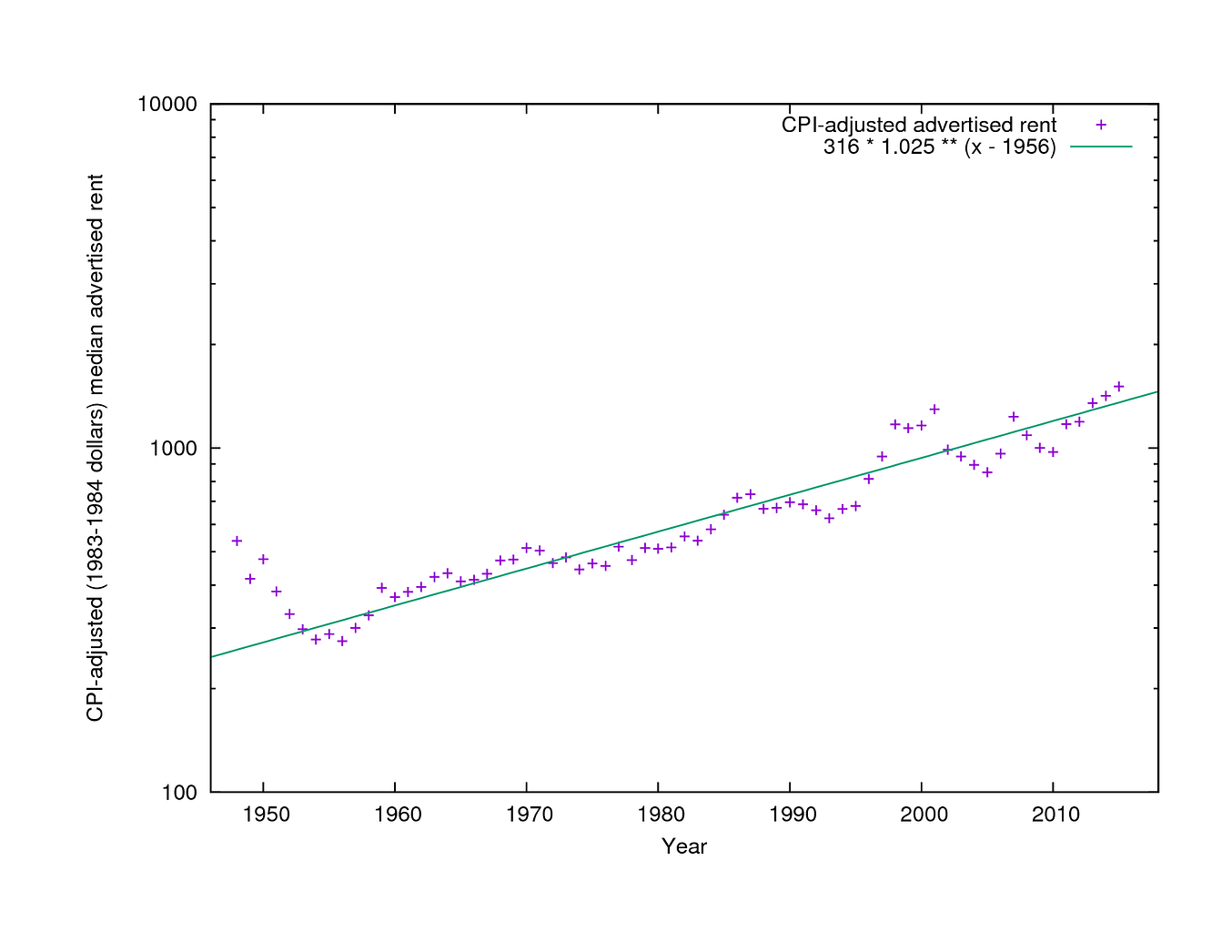

Instead of getting any further into that, this blog post exists to re-emphasize what his new data revealed: this chart

That, my friends, is 70 years of San Francisco housing prices. There are some ups and downs, but for the most part there is a very simple trend: 6.6 percent.

That’s the amount the rent has gone up every year, on average, since 1956. It was true before rent control; it was true after rent control. It wasn’t entirely true during the 2000 tech bubble, but it was still sort of true and it became true again afterward.

6.6 percent is 2.5 percentage points faster than inflation, which doesn’t seem like a lot but when you do it for 60 years in a row it means housing pricesquadruple compared to everything else you have to buy.

That’s bad. But that’s SF today, compared to 1956.

So what caused prices to go up? That’s the really exciting part of Fischer’s discovery. Armed with his data, he more or less answered that question. Continue reading

The super-rich inevitably pops the housing bubble

The bigger the bubble, the longer the hangover.

But what would happen if they did actually go? As Danny Dorling, the Oxford professor of geography, notes, the ultra-moneyed classes do abandon cities – “at a time of their choosing”. Long Island was once so rich as to be the setting for the Great Gatsby – until the crash of 1929. Now the grand houses remain but the big-money holidays at the Hamptons. (For more data, look at Dorling’s new book A Better Politics, free online here.) The other thing we know is that cities that get too high on speculation face a long, long hangover.

Continue reading

London a city of renters

One of Britain’s most respected thinktanks, the Resolution Foundation, has been digging through the government’s own figures and given me exclusive access to its analysis for the capital. Perhaps its single biggest finding is this: the proportion of Londoners who own a home with a mortgage has been sliding since the early 90s – and has now dipped below the number who rent privately. In John Major’s time, less than 20% of all Londoners rented privately, now that is in the mid-30s, and marching up to 40%.

In other words, the idea that Generation Rent is the one with the problem is for the birds: London is becoming a city of renters. Nor is that trend likely to reverse. The consultancy PricewaterhouseCoopers predicts that, in less than 10 years, 60% of the capital will be renting from a private landlord or a housing association. Continue reading

The UK housing crisis

American Poverty

Recently, the Brookings Institution published a report looking at the same idea but giving it a different name. The paper, builds on research from the British economist William Beveridge, who in 1942 proposed five types of poverty: squalor, ignorance, want, idleness, and disease. In modern terms, these could be defined as poverty related to housing, education, income, employment, and healthcare, respectively. Analyzing the 2014 American Community Survey, the paper’s co-authors, Richard Reeves, Edward Rodrigue, and Elizabeth Kneebone, found that half of Americans experience at least one of these types of poverty, and around 25 percent suffer from at least two. Continue reading

The London Fairness Commission’s Final Report

London is a global city, yet compared to other cities of its standing the cost of living in London is high. Londoners on average salaries spend 49% of their pay on rent, compared with 26% for those on average salaries outside the capital. The average extra costs for householders who are renting and using childcare is £6,000. Would-be homeowners in London need to earn £77,000 a year to get on the housing ladder[1]. Across the UK, a first-time buyer needs a minimum income of £41,000.

The London Fairness Commission’s recommendations include: Continue reading