Retired Army Gen. Richard Cody, a vice president at L-3 Communications, the seventh largest U.S. defense contractor, explained to shareholders in December that the industry was faced with a historic opportunity. Following the end of the Cold War, Cody said, peace had “pretty much broken out all over the world,” with Russia in decline and NATO nations celebrating. “The Wall came down,” he said, and “all defense budgets went south.”

Now, Cody argued, Russia “is resurgent” around the world, putting pressure on U.S. allies. “Nations that belong to NATO are supposed to spend 2 percent of their GDP on defense,” he said, according to a transcript of his remarks. “We know that uptick is coming and so we postured ourselves for it.”

Continue reading

Tag Archives: USA

The Case for a Financial Transactions Tax

The report argues:

- A financial transactions tax could likely raise over $105 billion annually (0.6 percent of GDP) based on 2015 trading volume. This estimate is roughly in the middle of recent estimates that ranged from as high as $580 billion to as low as $30 billion.

- The full amount of this tax would be borne by the financial industry, and not individual holders of stock or pension funds and other institutional investors. Evidence suggests that trading volume is elastic with respect to price, meaning that any drop in trading volume resulting from the tax would reduce costs for end users by a larger amount than the tax would increase them.

- It is reasonable to believe that the industry would be no less effective in serving its productive use (allocating capital) after the tax is in place. This means that one of the primary effects of the tax would be to reduce waste in the financial sector, reducing costs while having little or no effect on its principal purpose: to allocate capital effectively.

- The revenue raised through an FTT would easily be large enough to cover the cost of free college tuition (among other social programs), although if nothing were done to stem the growth rate of college costs, it would eventually prove inadequate.

The report also notes that the financial sector is the main source of income for many of the highest earners in the economy. This means that downsizing the industry through an FTT could play an important role in reducing income inequality.

The mission of the F-35

The F-35 Joint Strike Fighter is possibly one of the most useless jets and biggest waste of taxpayer money ever conceived by the US military. In fact, according to Pierre Sprey, one of the three men that created the F-16, the point of this plane is “to spend money.” He clarifies, “that is the mission of the airplane, is for the US Congress to send money to Lockheed [Martin].”

The Surprisingly Swift Decline of US Manufacturing Employment

So why did American trade policy make such a big difference, even though tariffs didn’t fall? Pierce and Schott can’t say for sure, but they speculate that it has to do with patterns of investment.

Giving Chinese companies confidence that tariffs would stay low encouraged them to invest in production capacity aimed at supplying the American market. And giving American companies confidence that tariffs would stay low encouraged them to build supply chains around Chinese manufacturers.

USA, Militization, Japan

Former CIA Officer Amaryllis Fox’s lesson from undercover life

Illegal drug profits, Washington’s foreign military outflows of dollars, and US balance of payments deficit

Hudson’s next task was to estimate the amount of money from crime going into Switzerland’s secret banking system. In this investigation, his last for Chase, Hudson discovered that under US State Department direction Chase and other large banks had established banks in the Caribbean for the purpose of attracting money into dollar holdings from drug dealers in order to support the dollar (by raising the demand for dollars by criminals) in order to balance or offset Washington’s foreign military outflows of dollars. If dollars flowed out of the US, but demand did not rise to absorb the larger supply of dollars, the dollar’s exchange rate would fall, thus threatenting the basis of US power. By providing offshore banks in which criminals could deposit illicit dollars, the US government supported the dollar’s exchange value.

Continue reading

Cerberus and the profits of mass murder

But Cerberus is also very big in guns. It is run by people for whom everything is just business, from firesales to firearms, from Irish property deals to selling weapons of war to anyone who wants them. The connection between Belfastand Orlando reminds us of a truth that is easily forgotten – behind every mass shooting by a deranged psychopath in the US is a very profitable industry owned by Ivy League graduates with clean hands and manicured nails, respectable people who fund politicians in Congress and host charity galas inManhattan. If they had a slogan it would be the old Roman adage, pecunia non olet – money has no smell.

Continue reading

F-18 fighter jet – a “nice margin generator.”

“F-18 has been a great program for this company and continues to be,” CFO Ken Bedingfield told investors this week at Citi’s Industrials Conference in Boston, adding that it’s also a “nice margin generator.”

Continue reading

UBI isn’t really about welfare spending: It’s about tax policy. And it is affordable.

This would be a sound argument if it didn’t miss the point. UBI isn’t really about welfare spending: It’s about tax policy.

UBI is an unconditional cash transfer, which means that you get money from the government to spend however you want. That’s an unusual government spending program. In the US, besides Social Security, the government usually either spends money on a service (like health care or education) or gives conditional cash in the form of things like food stamps.

But the government also spends a lot of money each year on cash transfers through “tax expenditures,” which is the money the government doesn’t collect in taxes because of exclusions in the tax code. Except for the Earned Income Tax Credit, those expenditures almost always help the rich more than the poor. By replacing them with UBI, we would create a more progressive system. That, not the elimination of all government programs, should be the starting place for debates about UBI. Continue reading

The case for Universal Basic Income

But, after a Conservative government ended the project, in 1979, Mincome was buried. Decades later, Evelyn Forget, an economist at the University of Manitoba, dug up the numbers. And what she found was that life in Dauphin improved markedly. Hospitalization rates fell. More teen-agers stayed in school. And researchers who looked at Mincome’s impact on work rates discovered that they had barely dropped at all. The program had worked about as well as anyone could have hoped.

Mincome was a prototype of an idea that came to the fore in the sixties, and that is now popular again among economists and policy folks: a basic income guarantee. There are many versions of the idea, but the most interesting is what’s called a universal basic income: every year, every adult citizen in the U.S. would receive a stipend—ten thousand dollars is a number often mentioned. (Children would receive a smaller allowance.)

One striking thing about guaranteeing a basic income is that it’s always had support both on the left and on the right—albeit for different reasons. Martin Luther King embraced the idea, but so did the right-wing economist Milton Friedman, while the Nixon Administration even tried to get a basic-income guarantee through Congress. These days, among younger thinkers on the left, the U.B.I. is seen as a means to ending poverty, combatting rising inequality, and liberating workers from the burden of crappy jobs. For thinkers on the right, the U.B.I. seems like a simpler, and more libertarian, alternative to the thicket of anti-poverty and social-welfare programs. Continue reading

The decline of Britain; EU

Because we had survived the war intact we did not realise fully the motives or strength of the European search for unity. We underestimated the recovery powers of the continental countries and the great boost that could be given to their industrial development by membership of a common market. We overlooked one of the prime lessons of our own history, that we had been able to spearhead the industrial revolution in the eighteenth century, not because of our size—we only had a third of the population of France—but because, at a time when the countries of the continent were fragmented by internal tolls and tariff barriers, we were the biggest single market in Europe. We did not perceive fully how the Commonwealth would evolve and the reduced political and economic role that we would have in it. (For instance, we were taken aback when, in 1957, our proposal for a British-Canadian free trade area was turned down by Ottawa.) Continuing for long to believe that we had a unique part to play on the world scene because of our participation in Churchill’s three interlocking circles, we were concerned that too close a relationship with Europe would weaken our influence in the other two circles, those of the Commonwealth and America. Continue reading

The (American) coporate take-over of Britain and EU

By comparison with the British system, however, this noxious sewer is a crystal spring. Every stream of corporate effluent with which the EU poisons political life has a more malodorous counterpart in the UK. The new Deregulation Act, a meta-law of astonishing scope, scarcely known and scarcely debated, insists that all regulators must now “have regard to the desirability of promoting economic growth”. Rare wildlife, wheelchair ramps, speed limits, children’s lungs: all must establish their contribution to GDP. What else, after all, are they for?

Tax Justice: Millionaires Less Mobile than the Rest of Us

Stanford University researchers teamed with officials at the Treasury Department to examine every tax return reporting more than $1 million in earnings in at least one year between 1999 and 2011. They found that while 2.9 percent of the general population moves to a different state in a given year, just 2.4 percent of millionaires do so. Even more striking is that for the most “persistent millionaires” (those earning over $1 million in at least 8 years of the researchers’ sample), the migration rate is just 1.9 percent per year. As the researchers explain: “millionaires are not searching for economic opportunity—they have found it.” …

In other words, Florida is only one of the nine states without broad-based income taxes that seems to possess any kind of special allure for high-income taxpayers. Given that reality, the study notes that “It is difficult to know whether the Florida effect is driven by tax avoidance, unique geography, or some especially appealing combination of the two.” In any case, this study refutes the notion that repealing state income taxes can transform a state into a magnet for high-income taxpayers: it’s simply not playing out that way in eight of the nine states without such a tax. …

This research, of course, should all but kill the thesis that you just have to cut taxes on rich folk for fear they’ll flee to more hospitable climes. But this thesis is just too convenient for too many wealthy people, and it’s been successfully put out of its misery many times before – then sprung back to life the next time around. This isn’t the last we’ve seen of it.

New Research Shows Millionaires Less Mobile than the Rest of Us

http://www.taxjustice.net/2016/05/27/new-research-shows-millionaires-less-mobile-than-the-rest-of-us/

Global nuclear weapons 2016

At the start of 2016 nine states—the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, China, India, Pakistan, Israel and North Korea—possessed approximately 4,120 operationally deployed nuclear weapons. If all nuclear warheads are counted, these states together possessed a total of approximately 15,395 nuclear weapons compared with 15,850 in early 2015 (see table 1).

Continue reading

Housing Bubble: 3 factors that determines the rent prices

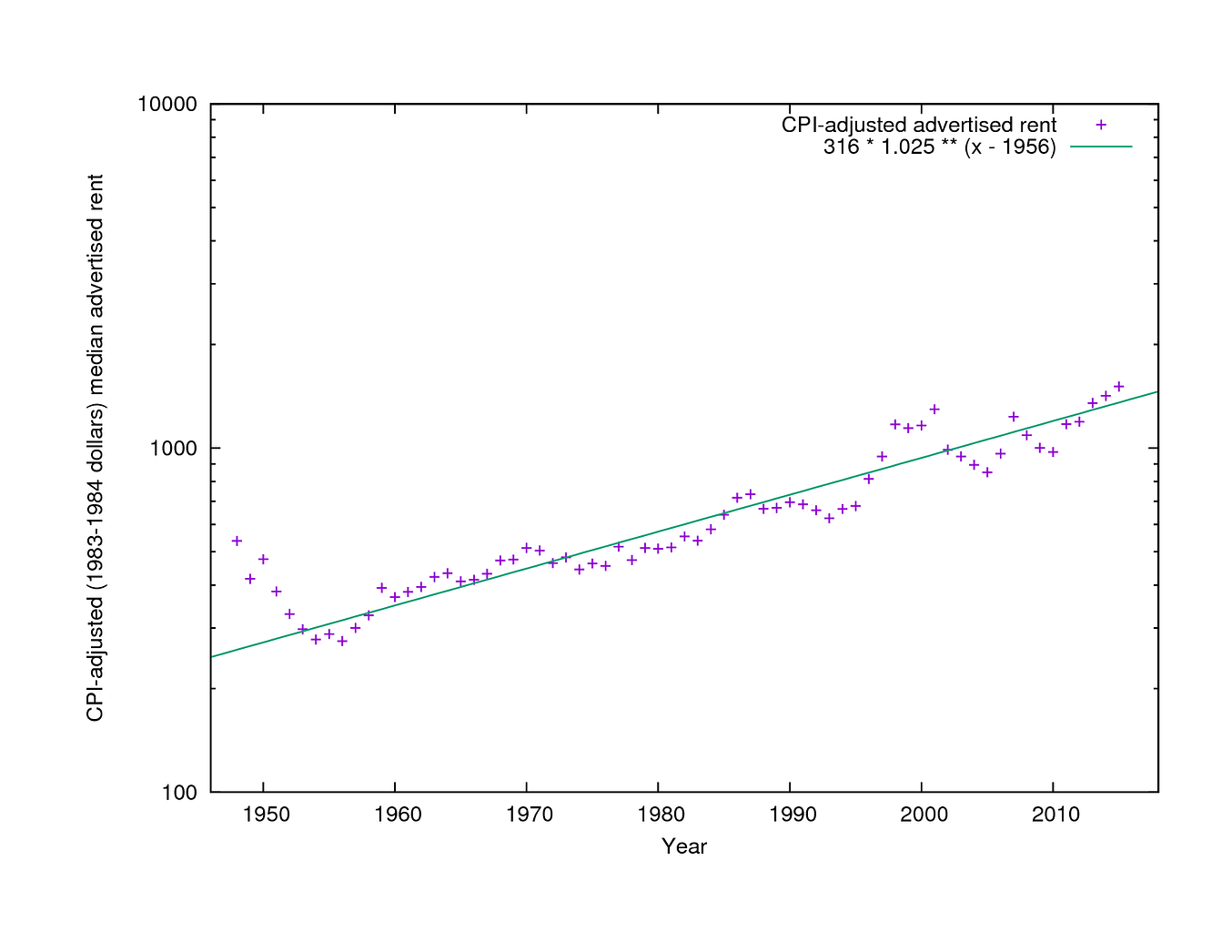

Instead of getting any further into that, this blog post exists to re-emphasize what his new data revealed: this chart

That, my friends, is 70 years of San Francisco housing prices. There are some ups and downs, but for the most part there is a very simple trend: 6.6 percent.

That’s the amount the rent has gone up every year, on average, since 1956. It was true before rent control; it was true after rent control. It wasn’t entirely true during the 2000 tech bubble, but it was still sort of true and it became true again afterward.

6.6 percent is 2.5 percentage points faster than inflation, which doesn’t seem like a lot but when you do it for 60 years in a row it means housing pricesquadruple compared to everything else you have to buy.

That’s bad. But that’s SF today, compared to 1956.

So what caused prices to go up? That’s the really exciting part of Fischer’s discovery. Armed with his data, he more or less answered that question. Continue reading

Sectoral balances and Clinton’s budget surplus

A sectoral balances analysis starts with the recognition that the U.S. economy, like any national economy, is roughly comprised of three sectors. There’s the government sector: the federal government, the Federal Reserve, and the state and local governments. There’s the private domestic sector: individuals, households, businesses, the banks, all the major industries, etc. And then there’s the foreign sector: i.e. the rest of the world, or every entity outside the U.S. national border that we trade with.

Each of these three sectors are in a state of surplus or deficit at any given moment. The government is either taxing more than it spends (surplus) or spending more than it taxes (deficit). Households and businesses in the private domestic sector are either saving more than they’re spending (surplus) or vice versa (deficit). And the rest of the world is either exporting more to America than it imports (surplus), or importing from the U.S. more than it exports (deficit). (Perhaps confusingly, the foreign sector balance is the inverse of the U.S. trade balance; i.e. a surplus in the foreign sector actually means a U.S. trade deficit.)

The consumption boom in the USA is all about healthcare

Basic Income, Bullshit Jobs, Poverty and Military Spending

To begin with, basic income would give us all genuine freedom. Nowadays, numerous people are forced to spend their entire working lives doing jobs they consider to be pointless. Jobs like telemarketer, HR manager, social media strategist, PR advisor, and a whole host of administrative positions at hospitals, universities, and government offices. “Bullshit jobs,” the anthropologist David Graeber calls them. They’re the jobs that even the people doing them admit are, in essence, superfluous.

And we’re not talking about just a handful of people here. In a survey of 12,000 professionals by the Harvard Business Review, half said they felt their job had no “meaning and significance,” and an equal number were unable to relate to their company’s mission. Another recent poll among Brits revealed that as many as 37% think they have a bullshit job. Continue reading

Corruption in military aid programs

One issue that is ripe for attention is the effect corruption has on military aid programs. Providers of such assistance need to take more care to ensure that their partners are not subverting the purpose of these programs by engaging in corrupt practices.

U.S. military aid programs are a case in point. According to data compiled by the Security Assistance Monitor, this year the United States is providing over $8 billion in arms and training to 50 of the 63 nations that Transparency International has identified as being at “high” or “critical” risk of corruption in their defense sectors. …

Widespread corruption poses other serious challenges to providers of military assistance. There is a danger that tilting aid too heavily toward the defense sector can strengthen it at the expensive of civilian institutions, undermining civilian control of the military. There is a significant risk that this may be occurring among key recipients of U.S. security assistance. The Security Assistance Monitor’sassessment of dependence on U.S. military aid demonstrates that, for 2014, U.S. military aid accounted anywhere from 15% to 20% of defense expenditures of recipient countries like Egypt, Pakistan, and Burundi; over 50% in Liberia; and over 90% in Afghanistan. …

Corruption in defense assistance programs is about more than just a diversion of funds. It is also a threat to local, regional, and global security. Any effort to reduce global corruption must make cleaning up corruption in military aid programs a top priority.

Corruption in Military Aid Undermines Global Security

http://lobelog.com/corruption-in-military-aid-undermines-global-security/