The King’s Fund suggest that a 3.5% annual real-terms rise in NHS expenditure, combined with the provision of ‘moderate’ and ‘higher’ social care needs free at the point of use, would bring total health and social care expenditure up to between 11 and 12 per cent of UK GDP by 2025. This compares with the 16.9% of GDP spent by the US and the 11% spent by France on healthcare alone in 2015.

If UK economic growth continues at an annual average of 2%, by 2025 GDP at 2013 prices will be around £2.2 trillion compared to £1.8 trillion in 2015, an increase of £400 billion. In 2013 terms an increase in spending on health and social care to 12% of GDP would represent around an additional £60-70 billion annual spend in 2025. Yet even with this increase in health and care expenditure, the nation as a whole would still have over an extra £300 billion to spend on all other goods and services, public and private. The King’s Fund’s recommendation is thus eminently affordable.

Continue reading

Category Archives: Attlee Nation

Foreign investment increases house prices

Average house prices in England and Wales have almost tripled in the last 15 years, from just over £70,000 in 1999 to about £215,000 in 2014. Apart from a reduction in 2009, at the height of the global financial crisis, house prices increased every year during this period. Behind this average lies considerable regional variation, with average prices in the prime London area of Kensington and Chelsea reaching £1.3 million in 2014. Continue reading

Brexit: British Business and Industries

The UK has long depended on heavy flows of investment from abroad to make up for the weaknesses in its own corporate and financial institutions. In 2015 the UK ran a deficit in its external trade in goods and services of 96 billion pounds ($146 billion in 2015), or 5.2 percent of GDP, the largest percentage deficit in postwar British historyand by far the largest of any of the G-7 group of industrialized economies. By comparison, the US ran a deficit of 2.6 percent of GDP, while Germany earned a surplus of 8.3 percent, Japan a surplus of 3.6 percent, and France broke even. In the memorable words of Mark Carney, the Canadian-born Governor of the Bank of England, the UK must depend on “the kindness of strangers” to remedy its trade gap.

The reason for this unusual dependency is that for decades the UK has been unable to produce enough goods that the rest of the world wants to buy. According to WTO statistics, between 1980 and 2011 the UK’s share of global manufacturing exports was halved, from 5.41 percent to 2.59 percent, so that by 2011, according to UN statistics, the dollar value of UK merchandise exports at $511 billion was not far off the level of Belgium’s at $472 billion, an economy with one six the UK’s population, (and not included in the Belgian figures, the value of German exports routed through Belgium ports).

Looking at export industries such as IT products, automobiles, machine tools, and precision instruments, all strongly dependent on advanced R&D and employee skills at all levels, the UK’s performance looks even worse. The period of 2005-2011 is especially revealing because it includes both the years of the Great Recession and the collapse of trade between the advanced industrial economies, but also years in which their trade with China and other BRIC economies such as India and Brazil grew rapidly. Since one of the chief claims of the Brexit campaigners has been that there are now these exciting new markets in BRIC countries waiting for British exporters to conquer, it is worth looking at how British companies actually performed during those years.

Underfunded NHS needed £3 billlion “working capital loans” from government last year

The government had to lend cash-strapped hospitals a record £2.825bn in the last financial year so they could pay staff wages, energy bills and for drugs needed to treat patients.

The Department of Health was forced to provide emergency bailouts on an unprecedented scale to two-thirds of hospital trusts in the 2015-16 financial year because they were set to run out of money, the Guardian can reveal.

Continue reading

PFI has sucked NHS funding dry

The NHS has more than 100 PFI hospitals. The original cost of these 100 institutions was around £11.5bn. In the end, they will cost the public purse nearly £80bn. The total UK PFI debt is over £300bn for projects worth only £55bn. This means that nearly £250bn will be spent swelling the coffers of PFI groups.

Continue reading

The sale of the Land Registry makes no sense

So the Land Registry is a natural monopoly and, as goes the Competition and Market Authority’s main argument, these kinds of services should be publically owned. Handing a monopoly over to a private company in search of profit risks harming consumers – the new owners may simply charge a higher price for the service, or in this case put the data, the Land Registry’s most valuable asset, behind a paywall.

The Law Society says that the Land Registry plays a central role in ensuring property rights in England and Wales, and so we need to ensure that it maintains its integrity and is free from any conflict of interest. Continue reading

Share of economic growth enjoyed by workers is at its lowest since the second world war

And the longer the slump goes on, the more the public tumbles to the fact that not only has growth been feebler, but ordinary workers have enjoyed much less of its benefits. Last year the rich countries’ thinktank, the OECD, made aremarkable concession. It acknowledged that the share of UK economic growth enjoyed by workers is now at its lowest since the second world war. Even more remarkably, it said the same or worse applied to workers across the capitalist west.

Housing Bubble: 3 factors that determines the rent prices

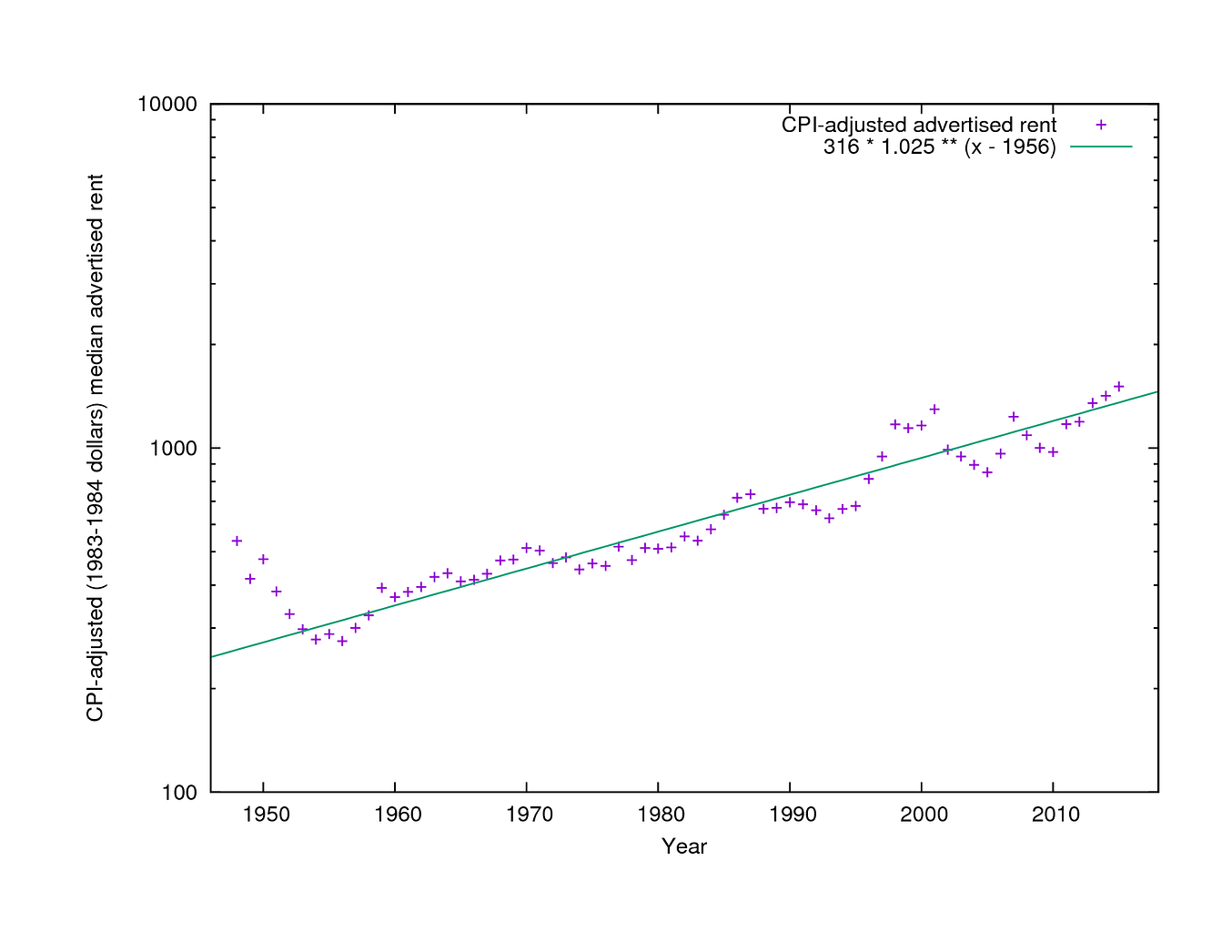

Instead of getting any further into that, this blog post exists to re-emphasize what his new data revealed: this chart

That, my friends, is 70 years of San Francisco housing prices. There are some ups and downs, but for the most part there is a very simple trend: 6.6 percent.

That’s the amount the rent has gone up every year, on average, since 1956. It was true before rent control; it was true after rent control. It wasn’t entirely true during the 2000 tech bubble, but it was still sort of true and it became true again afterward.

6.6 percent is 2.5 percentage points faster than inflation, which doesn’t seem like a lot but when you do it for 60 years in a row it means housing pricesquadruple compared to everything else you have to buy.

That’s bad. But that’s SF today, compared to 1956.

So what caused prices to go up? That’s the really exciting part of Fischer’s discovery. Armed with his data, he more or less answered that question. Continue reading

IMF: Neoliberalism and austerity policies don’t work

Osborne said his austerity programme would give the government more flexibility in the event of a future crisis, but the IMF said taking out this sort of insurance policy would only be worth it if the benefits exceeded the costs.

“It turns out, however, that the cost could be large – much larger than the benefit. The reason is that, to get to a lower debt level, taxes that distort economic behaviour need to be raised temporarily or productive spending needs to be cut – or both. The costs of the tax increases or expenditure cuts required to bring down the debt may be much larger than the reduced crisis risk engendered by the lower debt.”

The economists rejected the notion that austerity could be good for growth by boosting the confidence of the private sector to invest. It said that in practice, “episodes of fiscal consolidation have been followed, on average, by drops rather than by expansions in output. On average, a consolidation of 1% of GDP increases the long-term unemployment rate by 0.6 percentage points.” Continue reading

“Jeremy Corbyn is the best thing to happen to the Labour Party since Clement Atlee.”

“I want us to surpass even the Attlee government for radical reform”

Mr Corbyn called it “a new economics”. Mr McDonnell described his aim as being no less than the “fundamental business of reforming capitalism”.

So today was big on vision, but short on new detail. Perhaps no surprise with the next general election, in all likelihood, not until 2020.

No one can doubt their ambition: “I want us to surpass even the Attlee government for radical reform,” the shadow chancellor said, a reference to the administration that founded the NHS.

The super-rich inevitably pops the housing bubble

The bigger the bubble, the longer the hangover.

But what would happen if they did actually go? As Danny Dorling, the Oxford professor of geography, notes, the ultra-moneyed classes do abandon cities – “at a time of their choosing”. Long Island was once so rich as to be the setting for the Great Gatsby – until the crash of 1929. Now the grand houses remain but the big-money holidays at the Hamptons. (For more data, look at Dorling’s new book A Better Politics, free online here.) The other thing we know is that cities that get too high on speculation face a long, long hangover.

Continue reading

British railways – a privatisation scam

The economic historian Robert Millward points out that the popular notion of nationalisation in Europe as a 1940s phenomenon, driven by the perceived failures of capitalism in the 1930s and the successes of the planned economy in wartime, ignores the earlier history of state direction of the universal networks. Gladstone wanted to nationalise the railways in 1844. Even earlier, at their genesis, the railways were dependent on the state to force private landowners to yield right of way to the iron road. The problem of the publicly owned British railways after 1948 wasn’t that they were publicly owned, but that they were expected to do so many things for so many people, often for less than they actually cost, that it was no longer possible to be sure exactly what they were doing with their share of the nation’s resources, or why. What was clear was that they kept failing to meet one of their key targets, which was to break even.

Continue reading

What is Neoliberalism?

I know what I mean when I (occasionally) use the term neoliberal. Neoliberalism is a political movement or ideology that hates ‘big’ government, dislikes any form of market interference by the state, favours business interests and opposes organised labour. The obvious response to this is why ‘neo’. In the European tradition we could perhaps define that collection as being the beliefs of a (market) liberal (although that would be misleading for reasons I give below). The main problem here is that in US discourse in particular the word ‘liberal’ has a very different meaning. As Corey Robin writes, neoliberals

would recoil in horror at the policies and programs of mid-century liberals like Walter Reuther or John Kenneth Galbraith or even Arthur Schlesinger, who claimed that “class conflict is essential if freedom is to be preserved, because it is the only barrier against class domination.” Continue reading

London a city of renters

One of Britain’s most respected thinktanks, the Resolution Foundation, has been digging through the government’s own figures and given me exclusive access to its analysis for the capital. Perhaps its single biggest finding is this: the proportion of Londoners who own a home with a mortgage has been sliding since the early 90s – and has now dipped below the number who rent privately. In John Major’s time, less than 20% of all Londoners rented privately, now that is in the mid-30s, and marching up to 40%.

In other words, the idea that Generation Rent is the one with the problem is for the birds: London is becoming a city of renters. Nor is that trend likely to reverse. The consultancy PricewaterhouseCoopers predicts that, in less than 10 years, 60% of the capital will be renting from a private landlord or a housing association. Continue reading

The UK housing crisis

Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism sees competition as the defining characteristic of human relations. It redefines citizens as consumers, whose democratic choices are best exercised by buying and selling, a process that rewards merit and punishes inefficiency. It maintains that “the market” delivers benefits that could never be achieved by planning.

Attempts to limit competition are treated as inimical to liberty. Tax and regulation should be minimised, public services should be privatised. The organisation of labour and collective bargaining by trade unions are portrayed as market distortions that impede the formation of a natural hierarchy of winners and losers. Inequality is recast as virtuous: a reward for utility and a generator of wealth, which trickles down to enrich everyone. Efforts to create a more equal society are both counterproductive and morally corrosive. The market ensures that everyone gets what they deserve. Continue reading

NHS doctors’ open letter

After five years of a government which pledged to protect the NHS, this election campaign makes it timely to assess its stewardship, since 2010, of England’s most precious institution. Our verdict, as doctors working in and for the NHS, is that history will judge that this administration’s record is characterised by broken promises, reductions in necessary funding, and destructive legislation, which leaves health services weaker, more fragmented, and less able to perform their vital role than at any time in the NHS’s history.

In short, the coalition has failed to keep its NHS pledges.

The 2012 Health and Social Care Act is already leading to the rapid and unwanted expansion of the role of commercial companies in the NHS. Lansley’s Act is denationalising healthcare because the abolition of the duty to provide an NHS throughout England abdicates government responsibility for universal services to ad hoc bodies (such as clinical commissioning groups) and competitive markets controlled by private-sector-dominated quangos.

In particular, the squeeze on services is hitting patients. People may be unaware that under the coalition, dozens of Accident & Emergency departments and maternity units have been closed or earmarked for closure or downgrading. In addition, 51 NHS walk-in centres have been closed or downgraded in this time, and more than 60 ambulance stations have shut and more than 100 general practices are at risk of closure.

The core infrastructure of the NHS is also being eroded with the closure of hospitals and thousands of NHS beds since 2010.

Mental health and primary care are faring no better – with both in disarray due to funding cuts and multiple reorganisations driven by ideology, not what works. Public health has been wrenched out of the NHS, where it held the ring for coordinated and equitable services for so long.

In September 2014, the Royal College of General Practitioners said that the wait to see a GP is a “national crisis”.

In England the waiting list to see a specialist stands at 3 million people, and in December 2014 NHS England estimated that nearly 250,000 more patients were waiting for treatment across England who are not on the official waiting list.

Throughout England, patients have been left queueing in ambulances and NHS trusts have resorted to erecting tents in hospital car parks to deal with unmet need.

A&E target waiting times have not been met for a year, and are at the worst levels for more than a decade; and elderly, vulnerable patients are marooned in hospital because our colleagues in social care have no money or staff to provide much-needed services at home.

Funding reductions for local authorities (in some places reductions as high as 40%) have undermined the viability of many local authority social care services across England. This has resulted in more patients arriving at A&E and more patients trapped in hospital as the necessary social care support needed to ensure their safe discharge is no longer there.

The NHS is withering away, and if things carry on as they are then in future people will be denied care they once had under the NHS and have to pay more for health services. Privatisation not only threatens coordinated services but also jeopardises training of our future healthcare providers and medical research, particularly that of public health.

Given the obvious pressures on the NHS over the last five years, and growing public concern that health services now facing a very uncertain future, we are left with little doubt that the current government’s policies have undermined and weakened the NHS.

The way forward is clear: abolish all the damaging sections of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 that fragment care and push the NHS towards a market-driven, “out-for-tender” mentality where care is provided by the lowest bidder. Reversing this costly and inefficient market bureaucracy alone will save significant sums. Above all, the secretary of state’s duty to provide an NHS throughout England must be reinstated, as in Scotland and Wales.

As medical and public health professionals our primary concern is for all patients.

We invite voters to consider carefully how the NHS has fared over the last five years, and to use their vote to ensure that the NHS in England is reinstated.

Continue reading

The King’s Fund: Tackling the growing crisis in the NHS

The King’s Fund has identified three big challenges for the NHS in England:

Tories’ deception: NHS massively underfunded

The doctors’ union points out that the Department of Health’s budget to fund health in England will only have gone up by £4.5bn by 2020-21 compared to the current financial year, well below the £10bn extra the government has pledged to increase it by. …

The BMA bases its claim on joint projections by the King’s Fund, Nuffield Trust and Health Foundation thinktanks. They found that Osborne’s spending reviewlast November means that the Department of Health’s budget will rise by just £4.5bn during this parliament – to £120.9bn by 2020 – but that NHS England’s share of it to pay for frontline services will go up by £7.6bn to £108.9bn. Continue reading